Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Planning, Queen’s University Belfast

At first thought, every person on this planet might consider the term ‘nature’ as an easy word to describe. When you ask someone, ‘What is nature?’, they might come up with a sneer while responding, ‘You must be kidding… As clear as day… it is…’ and then the halts, stammers, or changing of subjects might start… If you ask your second question, such as ‘Do you think this garden is nature or a designed landscape?’, the hem-and-haw phase might start to surge… and if you go to your third question, which is somehow trickier such as ‘Do you think, we, as human beings are or have ever been a part of nature?’, it will be the coup de grace… you might face a face with an absolute tendency to dodge any definite yes or no answer… The mission is now complete… The point has been proven: ‘Nature’ is a massively complicated term.. there is no straightforward one-sentence answer to describe it/her.

In the global body of knowledge, the term ‘nature’ has been discussed for decades in various fields of study, including urbanism, landscape design, ecological studies, sociology, anthropology, cultural studies and psychology. Spelling out the term ‘nature’ is supposedly an as-easy-as-pie question that reckons its latent complexity as a ‘conceptually transcendent phenomenon’. While some definitions of this term have certain similarities, others entail several paradoxical aspects. Differences in the conceptualisation of nature can be well observed even among various definitions in a single field of study. As Smith (2008) noted,

“… the concept of nature is extremely complex and often contradictory. Nature is order and it is disorder, sublime and secular, dominated and victorious; it is totality and a series of parts, woman and object, organism and machine. Nature is a gift of God, and it is a product of its own evolution; it is a universal outside history and also the product of history, accidental and designed, wilderness and garden” (p 11).

This blog post aims to present a spectrum of the interpretations of nature and to discuss the human-nature relationships in an urban context. At one extreme, nature is viewed as the world of non-humans that is distinguishable from all human activities. At the other end of the spectrum, however, nature and human activities such as culture, are considered as non-separable and are believed to have an eternal and continuing integration. So, the main core of the debate is to deliberate on ‘Is there any wrong or right definition of the term nature? And why?’.

In its traditional definition and most common sense, nature refers to any non-human element that can be distinguished from human activities. According to this definition, nature is opposed to history, culture, convention and any other artificial work or product. Hence, nature is recognised as a stranger/foreigner, or more precisely, as an external scope with an ‘otherness’ to humanity. In this exclusion-based definition, the natural environment is composed of elements such as mountains, deserts and shorelines with their existing plants and animals, while the human or man-made environment integrates the world of cities, houses, buildings, factories, transport and commerce. Such binary definition, however, results in an uncertainty of credibility while thinking about indecisive examples such as stretches of cultivated farmlands, pieces of planted forests or partially logged areas, water reservoirs and artificial lakes, or an apartment with a roof garden or with a yard of flowers and an eco-tech high-rise. In other words, even a bilateral all-or-nothing definition ¾that sees the two worlds of human beings and nature as divided¾ can’t precisely depict the exact boundaries between them (Altman and Wohlwill, 1983; Anderson, 2010; Smith, 2008; Soper, 1995).

The practical approaches based on ‘human: non-nature world’ manifesto include but not limited to: a) exploitation of nature, which recognises nature as a place of free resources that can be used without restrictions or considering human’s long-term impact on the Planet; b) taming (controlling) nature, which recognises nature as a wild and hostile world that should be tamed/conquered to prevent or diminish its potential threatening devastations; c) scientific approach, which roots back in the 17th century literature that states the mastery of nature and discovering the natural rules as a divine responsibility indicated by God; d) protecting nature, which is an eco-centric or bio-centric approach that acknowledges nature as valuable world regardless of its utility for humans and thus has to be kept safe/protected from humankind; e) back to nature (poetic) approach that started to grow from late 19th century and its concept of the nature idolatry and worship and thus endeavours to insert nature into the city and the landscape, as the context from which the city has developed; and e) Biophilia as a restorative environmental approach which is also referred as green or sustainable design, that entails two complementary scenarios of minimising and mitigate the adverse environmental effects of modern construction and development; and recreating/restoring sufficient and satisfying contact between people and nature (Anderson, 2010; Fuller and Irvine 2010; Gaston, 2010; Goldsmith, 1996; Kellert, 2005; Ritchie and Thomas, 2009; Smith, 2008; Soper, 1995)

On the opposite extreme point in portraying the human-nature relationship, nature and culture are recognised as inseparable. This notion, however, raises many challenges about the reconciling factors and whether this is the issue of re-integration or an ever-since, eternal integration. To answer the question of the age/antiquity of this [re]integration, some seemingly warring, internal and external factors come into the picture, such as the technology and its application in the process of modernisation versus context-based factional and collective practices. In other words, and similar to End 1 in the spectrum, even when we reckon nature and culture as an integrated world, the differences between the denotations and connotations of the term ‘integration’ will emerge as soon as we decide to enter the hands-on phase in this human-nature relationship. This leads to the presence of different and sometimes divergent practical approaches for building human-nature relationships in our cities.

Some of these integration-based definitions of the human-nature world includes a) Marxist philosophy that considers nature as being consistently reshaped, reconstituted and reproduced in the process of commodification (destruction-to-reconstruction of first-nature to second-nature) in a wide range of scales from micro to macro levels; b) nature and culture intertwined as in aboriginal society, where no industrial or technological imprints can be found as the initial source/reason of integration, and nature and culture have never been separated in Indigenous tribes and societies while Homo sapiens has existed; and c) nature-culture consolidation in routines and rituals associated with the ancient civilisations where society has been spontaneously keeping and transferring their nature-dependent practices from one generation to another as an intergenerational heart-to-heart affinity between past, present and future (Anderson, 2010; Castree and Macmillan, 2001; Schmidt, 1971; Smith, 2008).

As noted above, even when referring to the literature/database that defines nature as the world of the non-human, specifying the exact boundaries between these two spheres is not possible. So, the next question is, ‘What could be an alternative in elucidation on the scopes of the two worlds of nature and human beings?’. My answer is portraying a ‘spectrum’ with different levels of integration and interaction between these two worlds. The acknowledgement of the existence of such a spectrum in the interaction between human beings and nature will create flexibility and inclusion in implications of the two terms (scopes), i.e. different levels of naturalne artificialness, rather than being totally natural or artificial. While some people believe that the planted forests of the countryside are natural areas, some refer to an inner-city park as an example of a piece of nature. These examples reveal an implicit acknowledgment of the existence of a spectrum in the interaction between human beings and nature. In other words, it is proposed that areas have different levels of naturalness vs. artificialness, rather than being totally natural or artificial. The following images clearly illustrate the concept of omitting the binary extremes (Two Ends) and replacing it with ‘not-totally-man-made’ and ‘not-totally-natural’ but with various weights of natural-ness vs artificiality.

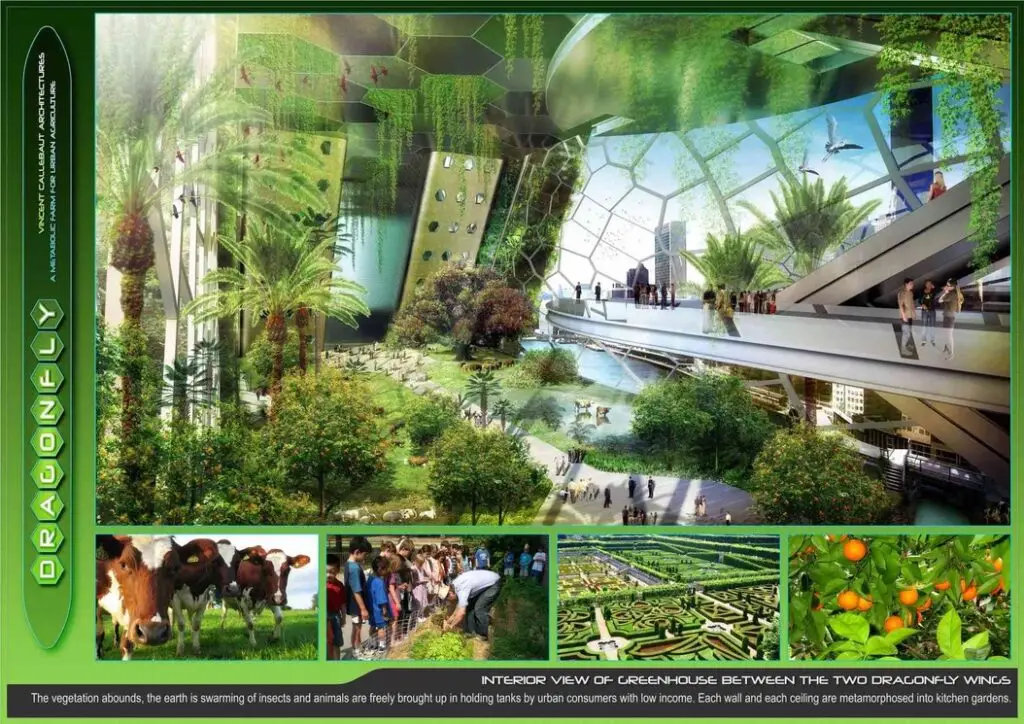

(Left) An example of inserted pieces of nature in seemingly completely artificial areas: Dragonfly: a 132-floor metabolic farm for urban agriculture in New York City, proposed in 2009, by Vincent Callebaut Architects (Source: Vincent Callebaut Architectures Paris, n.d.); (Right) an example of the footprints of human beings in seemingly completely natural areas: rice farms of the northern parts of Iran (Source: Rashidi, 2021)

Abstract diagram representing the spectrum of integration and interaction between human beings and nature (Source: Author)

If we accept that the existence of various levels of human-ness and natural-ness is inevitable/necessary in our human-nature interactions, then the next question is ‘What are the factors that have formed this oscillation/transcendence?’, and ‘How should we select the most appropriate approaches which can best respond to the mutual needs and preferences of the both worlds. In other words, the next challenge is what factors/influences have formed the variety of definitions for the human-nature relationship. Some of these influences are in common in the global context including but not limited to religious beliefs, industrialisation and modernisation through the process of urbanisation, literature, and socio-cultural praxis. The role of each individual factor, however, depends on the context of the study, the particular characteristics of its people and the natural structure under study. As a result, in each context, the first required measure to select suitable approach(es) is to explore the influences that have formed the ways of perceiving nature. The weights of these influences would then structure the preferences/prioritisation in selecting approaches. These approaches would create a complementary scenario to achieve a mutually supportive human-nature interaction.

As the last word, I would like to note that the nine human values of nature ¾that can be satisfied through the interaction of human beings and nature¾ endorse the possibility, or more precisely the necessity of using more than one approach towards nature which I call ‘approaches-combo’. Discussed by Kellert (1994), ‘each value reflects a host of physical and mental rewards derived from nurturing connection with natural systems and processes. Collectively, these values suggest that effective human-nature relations function as an anvil on which human fitness continues to be forged’ (p41). His debated nine values are Aesthetics (Physical appeal of and attraction to nature), Dominionistic (Mastery and control of nature), Humanistic (Emotional attachment to nature), Moralistic (Moral and spiritual relation to nature), Naturalistic (Direct contact with and experience of nature), Negativistic (Fear and aversion of nature), Scientific (Study and empirical observation of nature), Symbolic (Nature as a source of metaphorical and communicative thought), and Utilitarian (Nature as a source of physical and material benefit) (for further details see Kellert, 1999, p 41).

Disclosure: SPACE Studies is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.co.uk. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. This does not affect the price you pay.

Altman, I., & Wohlwill, J. F. (Eds.). (1983). Behavior and the Natural Environment. Plenum Press.

Anderson, J. (2010). Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces. Routledge. Available on Amazon.

Castree, N., & MacMillan, T. (2001). Dissolving Dualism: Actor-Networks and the Re-imagination of Nature. In N. Castree, & B. Braun (Eds.), Social Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics (pp. 208-224). Blackwell. Available on Amazon.

Fuller, R. A., & Irvine, K. N. (2010). Interaction between People and Nature in Urban Environments. In K. J. Gaston (Eds.), Urban Ecology (pp. 134-172). Cambridge University Press.

Gaston, K. J. (Eds.). (2010). Urban Ecology. Cambridge University Press.

Goldsmith, A. (1996). The Way: an Ecological World-view. Themis. Available on Amazon.

Kellert, S. R. (ed.) (2005). Building for Life, Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection. Washington, DC; London: Island Press. Available on Amazon.

Rashidi, M. R. (2021, May 11). Rice Farms in Gilan Province of Iran. IMNA NEWS. https://www.imna.ir/photo/492633/

Ritchie, A., & Thomas, R. (2009). Sustainable Urban Design: an Environmental Approach. Taylor & Francis. Available on Amazon.

Schmidt, A. (1971). The Concept of Nature in Marx. NLB. Available on Amazon.

Smith, N. (2008). Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space (3rd ed.). University of Georgia Press. Available on Amazon.

Soper, K. (1995). What is Nature?. Blackwell. Available on Amazon.

Vincent Callebaut Architectures Paris. (n.d). Dragonfly, a Metabolic Farm for Urban Agriculture, New York City, 2009, U.S.A.Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://vincent.callebaut.org/object/090429_dragonfly/dragonfly/projects

Dr Sanaz Shobeiri is an architect, urban designer, and landscape urbanist. She is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Planning of Queen’s University Belfast, working on a two-year research project: “Age-gender inclusiveness as a user-to-author metamorphosis in city centres: Belfast and Tehran”. I have been investigating the four interwoven layers of architectural/urban, historical, political, and sociocultural, as well as their consolidated role in restoring the inclusivity of urban spaces in city centres. Her research portfolio principally incorporates age-gender inclusiveness in city centres, the role of the human-nature relationship in design and planning, and the integration of sociocultural and environmental sustainability.

Sign in to continue

Not a member yet? Sign up now

Administrative Assistant

Deniz Bol is the Administrative Assistant at SPACE Studies, where she supports the day-to-day operations and contributes to the smooth functioning of the organization. Alongside her administrative role, Deniz is an artist with a passion for creative expression. She is currently pursuing her studies at the University of the Arts London (UAL), where she continues to develop her artistic practice. Her organizational skills, paired with her artistic background, make her a valuable asset to the SPACE Studies team, helping bridge the worlds of administration and creativity.

E-mail: denizbol@spacestudies.co.uk

Digital Marketing Consultant

Murat Oktay is the Digital Marketing Consultant at SPACE Studies, where he provides strategic guidance to enhance our digital presence and community engagement. With a keen eye for digital marketing trends and best practices, Murat plays a key role in refining our content strategy, expanding our online reach, and connecting with a wider audience. His expertise in digital tools and innovative marketing techniques aligns with SPACE Studies’ mission as a social enterprise, ensuring that our campaigns are impactful and resonate with our commitment to social responsibility in architecture and design. Outside his work with SPACE Studies, Murat stays at the forefront of digital marketing advancements, continually exploring new tools and sharing his insights with peers.

E-mail: muratoktay@spacestudies.co.uk

Marketing Manager

Santa Noella Matabaro is the Marketing Manager of SPACE Studies, bringing her expertise in strategic planning, community engagement, and relationship-building to the organization’s mission as a social enterprise. With a background in Politics & Law from the University of Kent, Santa combines analytical insights with a creative approach to advancing SPACE Studies’ vision of fostering interdisciplinary dialogue in architecture, design, and urban planning. In her role, she develops targeted campaigns and strategic partnerships, building brand presence and fostering meaningful connections with the community. Santa’s collaborative and people-centered approach enhances SPACE Studies’ impact, aligning with its commitment to social responsibility and innovation in the built environment.

Academic Content Coordinator

Betul Uckan is an architect and dedicated academic with a background in both architectural practice and research. She holds a Master of Science in Architectural Design and a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Istanbul Technical University, where she cultivated her interests in architectural theory and design. Betul has gained experience as a research assistant in various universities, contributing to design studios and foundational courses. She has also worked in the field as an architect with projects focused on design, modeling, and construction, and has been involved in notable projects, including Maltepe Piazza and Emaar Square in Istanbul. With her expertise spanning both digital and material architecture, Betul brings a dynamic, interdisciplinary approach to her role as the Academic Programme Coordinator.

E-mail: betuluckan@spacestudies.co.uk

Senior Researcher & Managing Editor

Arghavan Pournaderi is a senior researcher in the field of architectural conservation and restoration, with an academic foundation in architecture and specialized expertise in historic sites and buildings. Completing her PhD at the Art University of Isfahan, Iran, in 2019, her research has contributed to the understanding of Iran’s architectural heritage, with a focus on Isfahan’s urban and architectural evolution during the Safavid period. In addition to her extensive research, Dr. Pournaderi has held academic positions at various institutions in Isfahan, teaching at both undergraduate and graduate levels. Her work extends beyond academia as she contributes to SPACE Studies as Senior Researcher & Managing Editor, where she oversees scholarly initiatives that foster deeper interdisciplinary dialogue in architecture and heritage conservation.

Senior Researcher & Educational Consultant

Gregory Cowan is a Senior Researcher and Educational Consultant at SPACE Studies, where he leads initiatives that bridge academic research and practical application in architecture and urban design. He contributes his extensive experience to mentoring postgraduate students, designing educational workshops, and guiding community-focused projects. Gregory is also a freelance academic at the University of Wales Trinity St David and the University of Westminster, and founder of The Architects Coach. His expertise spans architectural workspace analysis, professional development, and positive intelligence coaching.

E-mail: gregorycowan@spacestudies.co.uk

Senior Researcher

Alison Hand is a Senior Researcher at SPACE Studies. She is a painter and writer with an MA in Painting from the Royal College of Art. Alison’s work focuses on creating absurd, unstable heterotopic spaces and dialogues with painting history. She is currently the Artist in Residence for King’s College London Philosophy Department on the Dreams and Wakeful Consciousness Research Project, exploring themes of time and simultaneity in new work. Alison has received numerous awards for her painting and is currently working with Bloomsbury Publishers on a major essay on Drawing in Contemporary Art. She is also the BA Fine Art Programme Leader at Art Academy London and co-director of Cement Arts. Her role at SPACE Studies involves leading research projects, mentoring junior researchers, and contributing to our artistic and academic initiatives.

E-mail: alisonhand@spacestudies.co.uk

Senior Researcher

Julian Wild is a Senior Researcher at SPACE Studies and the Sculpture Program Leader at The Art Academy London. With over 30 years of experience in creating and exhibiting sculptures, Julian has worked with high-profile clients such as Cate Blanchett and the University of Oxford. A fellow and former vice president (2015-2019) of the Royal Society of Sculptors, his work has been featured at venues like Modern Art Oxford and Chatsworth House. At SPACE Studies, Julian leads research projects, mentors junior team members, and conducts workshops that blend art and urban studies. In his free time, he enjoys attending academic conferences and crafting new sculptures.

E-mail: julianwild@spacestudies.co.uk

Director of Publications & Senior Researcher

Elif Suyuk Makakli (Associative Professor) earned her PhD in Architecture from the Vienna University of Technology, where she studied the impact of technology on architecture under Prof. William Alsop. With extensive experience in architectural practice in Istanbul and Vienna, she is now an Associate Professor at FMV Isik University, focusing on design education and technology. At SPACE Studies, Elif serves as both the Head of Publications and Senior Researcher, guiding scholarly content and contributing to research initiatives. She is dedicated to mentoring and fostering design innovation.

E-mail: elifsmakakli@spacestudies.co.uk

Director of Research

Sanaz Shobeiri is an architect, urban designer, and landscape urbanist, currently a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Planning at Queen’s University Belfast. Her research focuses on age-gender inclusiveness and the interplay of architectural, historical, political, and sociocultural dimensions in urban spaces, exemplified by her project on city centres in Belfast and Tehran. Sanaz holds a PhD in Urban Planning from the University of Tehran and has a robust portfolio in sustainability and urban theory. As Head of Research at SPACE Studies, she leads innovative research initiatives, fostering collaboration and academic excellence. In her free time, Sanaz enjoys exploring urban landscapes and supporting community development.

E-mail: sanazshobeiri@spacestudies.co.uk

Creative Director

Selin Gulce Sozmen is the Creative Director at SPACE Studies, where she leads the artistic vision and design strategy for the organisation. With a background in graphic design and visual arts, Selin has been instrumental in creating visually captivating books, journals, and event posters. Her role extends to developing and coordinating workshops and creative projects, ensuring that all visual materials meet the highest standards of quality and innovation. Selin’s dedication to creativity and excellence drives the visual and creative direction of SPACE Studies, making her an essential part of the team.

E-mail: selinsozmen@spacestudies.co.uk

Founder & Executive Director

Pinar Engincan is the Founder and Executive Director of SPACE Studies, an innovative social enterprise focused on fostering interdisciplinary dialogue and education in architecture and urban design. With extensive experience as a lecturer and researcher, Pınar holds a PhD in Architecture and has led numerous academic initiatives. Her career includes curriculum development, international collaborations, and research on housing and urban policies. Passionate about bridging academia and community, she champions accessible education and consultancy services, empowering individuals to shape the built environment.

E-mail: pengincan@spacestudies.co.uk